COTOPAXI, ECUADOR

John Quillen

19,347 feet

This is the second highest point in Ecuador, one of the highest active volcanoes in the world. Translated, Cotopaxi means "neck of the moon". During a full moon, the volcano crater appears to hold the planet. (Cotopaxi was incorporated into the course of the Raid Galluois adventure race. One of the most challenging adventure races on earth, 'The Raid' attracts some of the fittest racers on earth. The course organizers, however, underestimated the challenge that a climb of Cotopaxi presents. With nearly every team failing to reach the summit and famed racer Ian Adamson alone and reduced to tears on the summit organizers removed the climb as a mandatory part of the race, allowing racers to bypass this section. Do not underestimate the challenges of climbing a mountain of this size. copied from the web)

My goal was to follow a rigid acclimatization

plan en route to the top of Cotopaxi's summit crater. Beginning with a

smaller volcano, Pasochoa, I hiked with an outfitter to the 13,500 foot summit

from approximately 10,000 feet. Quito, Ecuador's capital, sits at

9500. It was a nice day and several hours of hiking to the summit which

afforded beautiful views of my ultimate destination. The ride to Pasochoa

was an adventure in itself characterized by a rickety four wheel drive tip up a

non existent road for the purpose of climbing a "new route".

Although I enjoyed the adventure, it was a portent of events that would unfold

throughout this South American expedition

. (the author atop Pasochoa with Cotopaxi in background)

(the author atop Pasochoa with Cotopaxi in background)

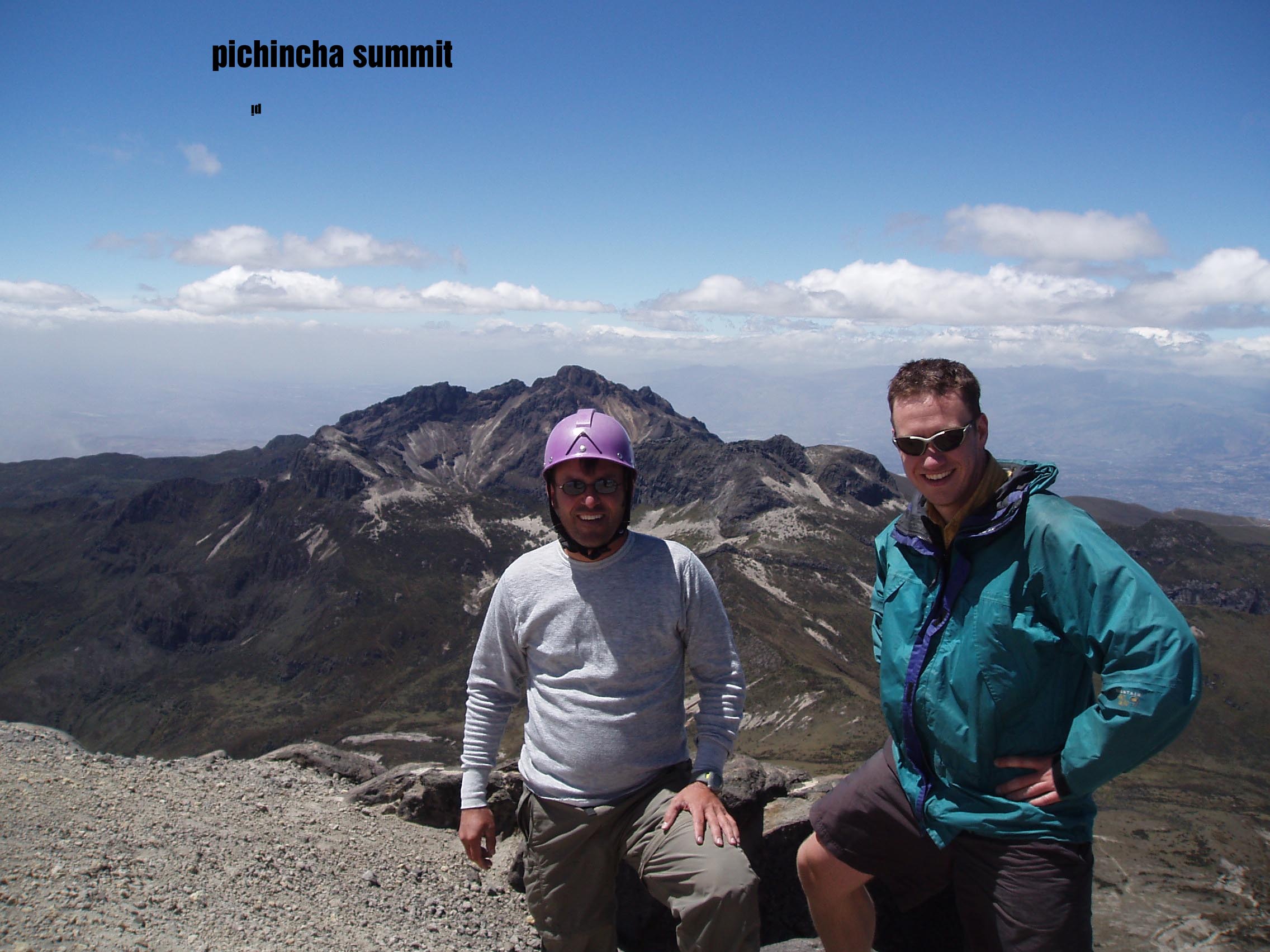

The next day, my second in Quito, was scheduled for a climb to Gagua Pichincha, which means "baby" pichincha. Gagua is an active volcano which last erupted four years prior to my visit and deposited a layer of ash about the city and disrupted the Ecuadoreans daily life for a few days. We began our climb to the summit from approximately 11,000 feet and followed a jeep road up to a hut. The thin air was definitely taking its toll on me as I paused for breath frequently with my companions. Apparently, the tour operator, Safari, had organized these hikes around my scheduled Cotopaxi climb. This was part of their "specialized" acclimatization program to ensure success upon Cotopaxi. So far so good. We took several hours to the first summit. Our team crosses the summit ridge of Gagua Pichincha)

(Summit Shot and view of volcano crater)

Now is when the "expedition" fell apart. Apparently, there wasn't enough interest in the next climb, Iliniza North to justify an expedition of one, namely myself. This is important, because the Ilinizas are relatively technical climbs. I had a taste of mild technical stuff on Pichincha and craved a little more. It was not to be. Furthermore, I was informed by the tour operator that there would be no more climbing until there was sufficient interest, e.g. money. I took this as my sign to go solo and secure alternate arrangements. After waiting a day in Quito and resting, I didn't want to lose valuable acclimatizing so I spoke with several outfitters, having anticipated such an occurrence beforehand. With the list of respected guides in hand, I was off to the shops back in Quito. After some haggling and testing of equipment and references, I secured the services of a guide named Robinson Solarri. He was ASEGIUM certified, although I did not meet him. He was on the mountain. Ecuador Explorer was to pick me up in the morning and transport me and gear to the National Park. I would meet him at the hut. My plan was reaching fruition.

As expected, I was summoned to the street from my hotel early Saturday morning and loaded gear into the truck and away we went. The mountain, although visible from Quito, is still several hours drive from the city. I was with two young fellows from Europe and their guide. They were all significantly younger than me, which made me somewhat uneasy. This had been the case on Rainier, so I shouldn't have been surprised. This is what happens when you adopt such a sport at the age of 38. After a brutal ride through the Nat'l Park and a wait at the border and some bribery of the park officials, we were parked at the base of Cotopaxi. The views here were excellent. Weather was another story. Most good climbs occur around the full moon as the weather is more stable at that time. I had also planned for this but the ring of clouds caused some unease. Apparently, this is the norm. When we drove up to 14000 feet, there was no more road. Our time for climbing had begun even though it would be but a "short" hike to the "Refugio" from whence all summit attempts are launched. To underestimate the hike to the Refugio is a mistake not likely repeated. After volunteering to carry extra gear and food, it was an hour to a building that was in plain site. I learned a valuable lesson right off the bat. Forget what you see here, it is more important to feel your way on this hill. The summit would appear equally close a t times the next day but equally distant and difficult.

We stowed our gear and I met Robinson. He had a seriousness that I liked and a lack of English that I didn't. We got one thing straight. Use of the word No. I made certain he understood that, for sure. He made sure I understood the word, "Now!" We were instant friends. It was off to review glacier skills with full crampons and ice axe. I had done all this before. The two boys from Europe had not. It would be a review plus some new skills. On Rainier, we never had to front point crampons. Here, with 45 degree slopes, this skill is a requisite and we reviewed extensively. While training with the "boys", our instructor (not my guide) kicked some scree rock loose which pounded my shin and hurt like hell. I was not wearing a helmet. They wouldn't give me a helmet. Said I wouldn't need it. Yeah, right. Pretty good knot, though. Getting my bad luck out of the way. After a couple of hours practice, it was back to the Refugio for dinner and then to bed for an alpine start around midnight. Of course I didn't sleep a wink. Never do on these adventures. Once you know what that next day is like, you are very nervous. Throughout the night, wind howled through the Refugio and clouds obscured the peak. It sounded downright cold. I went outside for the bathroom in sock feet. It was cool, but not bone chilling, although the thermometer showed below freezing. At midnight I began to assemble gear.

We began our climb to the glacier where we

donned crampons and roped up. The full moon made lights unnecessary and I

clipped into my private guide and quietly followed his footsteps. (a little visitor as we roped up at the start of the glacier)

(a little visitor as we roped up at the start of the glacier)

This began the rest step and pressure breathing section. I was doing all right at 15,500 feet, already higher than I had ever been before. In the middle of the night with the moon over my shoulder the assault was fully underway. It was decent going until we turned back to the left. That is when the traverse turned into a full blown climb. I saw the lights of rope teams above snaking through infinity towards the Heavens. They seemed miles away. Robinson and I were dragging up the rear. The Europe boys were ahead of us and moving fine. I was beginning to feel a bit nauseous. It was different this time, versus Rainier and Mt. Whitney, in that I felt as if the discomfort was lower. Coincidentally, my guide took an opportunity to stop and do what I felt like doing. I suppose he felt the need to remain alert, though, as he remained roped to me in the darkness of 2 a.m. Take your time, my friend, it was a nice break. Soon we were off again and I was stopping regularly. This air was getting thin. I could only move about fifteen steps before stopping to take that same number of breaths. My guide wasn't even huffing. We were moving straight uphill now, no traversing. The crevasses were becoming more frequent and I jumped a few of the just to keep up with Robinson. I remember my guide on Rainier commenting on our neophyte fear of crevasses. "Just jump across them" she said. Easy for her to say. I am from Tennessee. We don't have them here.

The next few hours were a blur of hypoxia and sleep. I found a way to actually sleep walk, provided that the terrain was consistent. In most places, this was a consistent steepness but broken, however, by crevasses and an occasional traverse. It was getting painful at this point as I awaited the arrival of the sun. The time was somewhere near 6 am. I was stopping more frequently and the guide was coaxing me with a different tone; a tone quite urgent. We were lagging behind. I was in pain and extremely tired. The lack of oxygen here is rather indescribable. You must take five breaths to compensate for one regular breath and that taxes your dry lungs. My water was frozen solid and that was just unacceptable. I tried to break up the chunks of ice before realizing how cold it really must have been. This made me shiver as the sweat rolled down my back. It was time to get going again.

. The sun rose and so did my spirits. This section held a flat spot that

jump-started a second wind. The sun warmed my body nicely but the summit appeared more

distant than ever.

The sun rose and so did my spirits. This section held a flat spot that

jump-started a second wind. The sun warmed my body nicely but the summit appeared more

distant than ever.

It was straight uphill now; no traversing on this

run. It was probably around 18,000feet. That's when we hit the

bottleneck. I took advantage of this rest point while watching teams climb

ahead of us. What I watched was a technical section of ice that required a

belay. Now we would front point the crampons and dig that ice axe while

holding it close to the neck of the shaft. You couldn't loose footing

here. It required all the focus I could muster. I couldn't look

down, only forward. A second wind was probably the result of a realization

that I must be nearing the summit, based on descriptions of this section. When I topped out, a rush of adrenaline surged through my body and suddenly I

felt strong. (winded, thirsty and bone tired, but confident). This

confidence was soon shattered with the presentation of the next technical

hurdle. A large crevasse apparently needed to be crossed by a ladder.

When I topped out, a rush of adrenaline surged through my body and suddenly I

felt strong. (winded, thirsty and bone tired, but confident). This

confidence was soon shattered with the presentation of the next technical

hurdle. A large crevasse apparently needed to be crossed by a ladder.

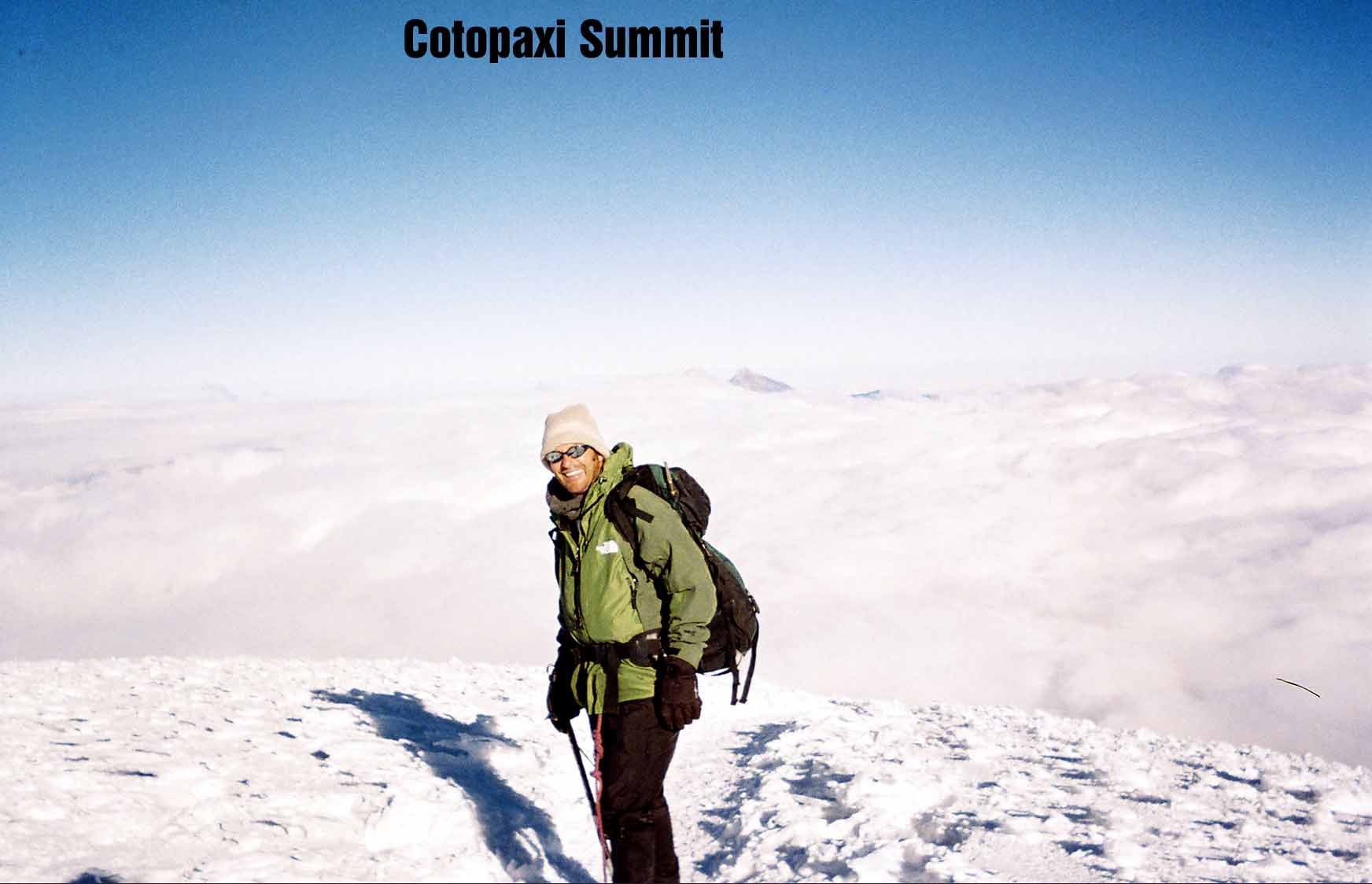

When I topped out on the ladder there was another hill. It was never ending. I didn't even pause, it was back into rest step and pressure breathing. Just go forward, there is no turning back. I huffed and puffed, pausing every few minutes, watching my feet, looking up no more. That is futility. Twenty more minutes, watching the feet, I felt them walking, not climbing. Then I looked up. There was no more up. I was there. I was at the top of Cotopaxi. The time was 7.30 am on July 25, 2005, exactly one year to the day that I summited Rainier with my climbing partner Martin Hunley.

I stood amongst the clouds, breathing heavily but feeling

light. I was too light headed to sit. There were five or six others

there on the summit. The clouds were below us and began to part. It

was a glorious day, beautiful and relatively

windless .

(summit shot)

(summit shot)

I had ten minutes at the top and the dubious distinction of being the last human to stand atop Cotopaxi on July 25, 2005. It was difficult to leave but summit time is precious. Getting up is optional, descent mandatory. It was time to descend. I drank a Gatorade which was not frozen. That was my only liquid for the day until we reached the Refugio some four hours later. There was a small incident upon descent. I took a fall and headed for a small crevasse. Robinson arrested my fall just as my feet hit the side wall of the crevasse. I didn't see it as life threatening or anything as I had already wedge my body lengthwise in case the arrest failed. It was an error of tired carelessness. We passed the European boys and were making good time towards the Refugio when their rope team took a fall. Their self-arrest held and they were visibly shaken. Our line of descent was apparently better and we hit the scree field first. It was wonderful to get out of the crampons and we all independently departed in the direction of the Refugio.

Maybe I should say, what I thought to be the direction of the Refugio. When you are that tired, it is simple to mistake paths etc. I passed the exit for the hut. Probably added a quarter mile to my descent. It was frustrating. My muscles were spent. It was after noon and began to spit snow. I carved a line in the loose sand and literally slid down to the Refugio in the sleet. People looked out of the hut to see me sitting on the rock wall while getting pelted with sleet. I couldn't' move for fifteen minutes. After packing my remaining stuff from the Refugio there was still the matter of the one hour descent from the hut. In the bad weather, I was having difficulty. Our group was waiting at the vehicle, in the rain. By now, at this elevation, it was raining. It felt nice, though, to be at 15,000 feet in the rain. My climb was complete. In four hours we would be riding the streets of Quito, basking in the glory of this beautiful Ecuadorian Summit Climb.